John Forrest on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

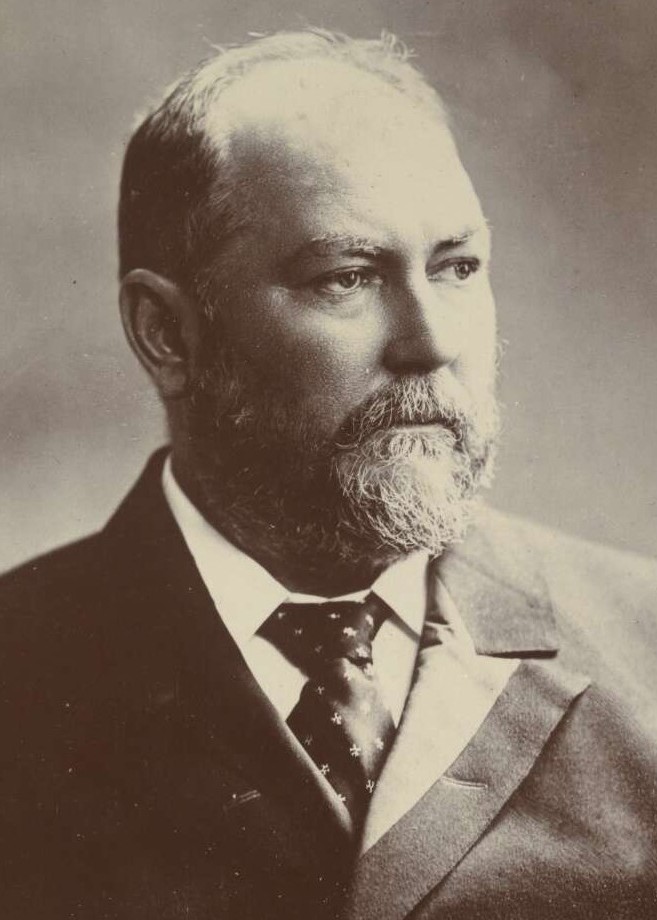

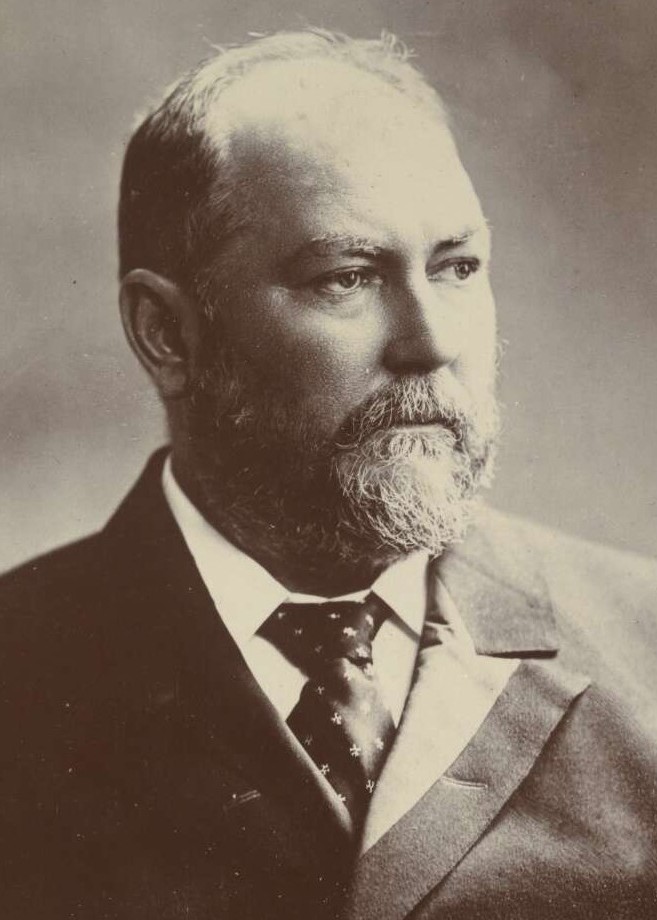

Sir John Forrest (22 August 1847 – 2 SeptemberSome sources give the date as 3 September 1918 1918) was an Australian explorer and politician. He was the first

Between 1869 and 1874, Forrest led three expeditions into the uncharted land surrounding the colony of Western Australia. In 1869, he led a fruitless search for the explorer

Between 1869 and 1874, Forrest led three expeditions into the uncharted land surrounding the colony of Western Australia. In 1869, he led a fruitless search for the explorer

Later that year, Forrest was selected to lead an expedition that would survey a land route along the

Later that year, Forrest was selected to lead an expedition that would survey a land route along the

In August 1872, Forrest was invited to lead a third expedition, from

In August 1872, Forrest was invited to lead a third expedition, from

He was an outstanding surveyor, and his successful expeditions had made him a popular public figure as well. Consequently, he was promoted rapidly through the ranks of the Lands and Surveys Department, and in January 1883 he succeeded

He was an outstanding surveyor, and his successful expeditions had made him a popular public figure as well. Consequently, he was promoted rapidly through the ranks of the Lands and Surveys Department, and in January 1883 he succeeded  Forrest's government also implemented a number of social reforms, including measures to improve the status of women, young girls and wage-earners. However, although Forrest did not always oppose proposals for social reform, he never instigated or championed them. Critics have therefore argued that Forrest deserves little credit for the social reforms achieved under his premiership. On political reform, however, Forrest's influence was unquestionable. In 1893, Forrest guided through parliament a number of significant amendments to the

Forrest's government also implemented a number of social reforms, including measures to improve the status of women, young girls and wage-earners. However, although Forrest did not always oppose proposals for social reform, he never instigated or championed them. Critics have therefore argued that Forrest deserves little credit for the social reforms achieved under his premiership. On political reform, however, Forrest's influence was unquestionable. In 1893, Forrest guided through parliament a number of significant amendments to the

On 30 December 1900, Forrest accepted the position of

On 30 December 1900, Forrest accepted the position of  Early in 1913, Deakin resigned as Leader of the Opposition. Forrest and Joseph Cook contested the leadership, with Cook winning by a single vote. Forrest was very disappointed, especially since Deakin, whom he considered a friend, had voted against him. Five months later, in the May 1913 federal election, the Liberal Party returned to power, with Cook as Prime Minister. Forrest was appointed treasurer for the third time. However, the government's majority of just one seat in the House of Representatives, along with Labor's large majority in the Senate, made it difficult to get anything done. In June 1914, Cook asked the Governor-General for a double dissolution, and Australia was sent back to the polls. Forrest retained his seat, but the Liberal Party was soundly defeated and Forrest was again relegated to the crossbenches.

In December 1916, a split in the Labor Party over conscription left Prime Minister Billy Hughes with a minority government. Hughes and his colleagues formed the

Early in 1913, Deakin resigned as Leader of the Opposition. Forrest and Joseph Cook contested the leadership, with Cook winning by a single vote. Forrest was very disappointed, especially since Deakin, whom he considered a friend, had voted against him. Five months later, in the May 1913 federal election, the Liberal Party returned to power, with Cook as Prime Minister. Forrest was appointed treasurer for the third time. However, the government's majority of just one seat in the House of Representatives, along with Labor's large majority in the Senate, made it difficult to get anything done. In June 1914, Cook asked the Governor-General for a double dissolution, and Australia was sent back to the polls. Forrest retained his seat, but the Liberal Party was soundly defeated and Forrest was again relegated to the crossbenches.

In December 1916, a split in the Labor Party over conscription left Prime Minister Billy Hughes with a minority government. Hughes and his colleagues formed the

Forrest had a rodent ulcer removed from his left temple in January 1915, which was initially thought to be non-malignant. Another operation followed in Perth in March 1917, but the cancer returned. He had a third operation in January 1918, after which he was hospitalised for nearly two weeks. The surgeons buried

Forrest had a rodent ulcer removed from his left temple in January 1915, which was initially thought to be non-malignant. Another operation followed in Perth in March 1917, but the cancer returned. He had a third operation in January 1918, after which he was hospitalised for nearly two weeks. The surgeons buried

He was a tall, heavily built man; in his later years, he tended towards stoutness, and he had a mass of about when he died. He was fond of pomp and ceremony and insisted on being treated with respect at all times. Highly sensitive to criticism, he hated having his authority challenged and tended to browbeat his political opponents. He had very little sense of humour and was greatly offended when a journalist playfully referred to him as the "Commissioner for Crown Sands".

His upbringing and education were said by his biographer, F. K. Crowley, to have compounded in him "social snobbery, laissez-faire capitalism, sentimental royalism, patriotic Anglicanism, benevolent imperialism and racial superiority." He was, however, a very popular figure who treated everyone he met with politeness and dignity. He was renowned for his memory for names and faces and for his prolific letter-writing.

However, as reported in ''

He was a tall, heavily built man; in his later years, he tended towards stoutness, and he had a mass of about when he died. He was fond of pomp and ceremony and insisted on being treated with respect at all times. Highly sensitive to criticism, he hated having his authority challenged and tended to browbeat his political opponents. He had very little sense of humour and was greatly offended when a journalist playfully referred to him as the "Commissioner for Crown Sands".

His upbringing and education were said by his biographer, F. K. Crowley, to have compounded in him "social snobbery, laissez-faire capitalism, sentimental royalism, patriotic Anglicanism, benevolent imperialism and racial superiority." He was, however, a very popular figure who treated everyone he met with politeness and dignity. He was renowned for his memory for names and faces and for his prolific letter-writing.

However, as reported in ''

Forrest's legacy can be found in the Western Australian landscape, with many places named by or after him:

* the small settlement of Forrest on the

Forrest's legacy can be found in the Western Australian landscape, with many places named by or after him:

* the small settlement of Forrest on the

Forrest, John (Sir) (1847–1918)

National Library of Australia, ''Trove, People and Organisation'' record for John Forrest * {{DEFAULTSORT:Forrest, John 1847 births 1918 deaths Australian explorers Burials at Karrakatta Cemetery Deaths from cancer Colonial Secretaries of Western Australia Commonwealth Liberal Party politicians Explorers of Western Australia People educated at Hale School Australian Knights Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George Australian politicians awarded knighthoods Members of the Australian House of Representatives for Swan Members of the Australian House of Representatives Members of the Cabinet of Australia Australian members of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom Members of the Western Australian Legislative Assembly Members of the Western Australian Legislative Council People from Bunbury, Western Australia Premiers of Western Australia Protectionist Party members of the Parliament of Australia Surveyors General of Western Australia Treasurers of Australia Australian federationists People who died at sea Treasurers of Western Australia Independent members of the Parliament of Australia Commonwealth Liberal Party members of the Parliament of Australia Nationalist Party of Australia members of the Parliament of Australia Defence ministers of Australia Goldfields Water Supply Scheme 20th-century Australian politicians

premier of Western Australia

The premier of Western Australia is the head of government of the state of Western Australia. The role of premier at a state level is similar to the role of the prime minister of Australia at a federal level. The premier leads the executive bra ...

(1890–1901) and a long-serving cabinet minister in federal politics.

Forrest was born in Bunbury, Western Australia

Bunbury is a coastal city in the Australian state of Western Australia, approximately south of the state capital, Perth. It is the state's third most populous city after Perth and Mandurah, with a population of approximately 75,000.

Located a ...

, to Scottish immigrant parents. He was the colony's first locally born surveyor, coming to public notice in 1869 when he led an expedition into the interior in search of Ludwig Leichhardt

Friedrich Wilhelm Ludwig Leichhardt (), known as Ludwig Leichhardt, (23 October 1813 – c. 1848) was a German explorer and naturalist, most famous for his exploration of northern and central Australia.Ken Eastwood,'Cold case: Leichhardt's dis ...

. The following year, Forrest accomplished the first land crossing from Perth

Perth is the capital and largest city of the Australian state of Western Australia. It is the fourth most populous city in Australia and Oceania, with a population of 2.1 million (80% of the state) living in Greater Perth in 2020. Perth i ...

to Adelaide

Adelaide ( ) is the capital city of South Australia, the state's largest city and the fifth-most populous city in Australia. "Adelaide" may refer to either Greater Adelaide (including the Adelaide Hills) or the Adelaide city centre. The dem ...

across the Nullarbor Plain

The Nullarbor Plain ( ; Latin: feminine of , 'no', and , 'tree') is part of the area of flat, almost treeless, arid or semi-arid country of southern Australia, located on the Great Australian Bight coast with the Great Victoria Desert to its ...

. His third expedition in 1874 travelled from Geraldton

Geraldton ( Wajarri: ''Jambinu'', Wilunyu: ''Jambinbirri'') is a coastal city in the Mid West region of the Australian state of Western Australia, north of the state capital, Perth.

At June 2018, Geraldton had an urban population of 37,648. ...

to Adelaide through the centre of Australia. Forrest's expeditions were characterised by a cautious, well-planned approach and diligent record-keeping. He received the Patron's Medal

The Royal Geographical Society's Gold Medal consists of two separate awards: the Founder's Medal 1830 and the Patron's Medal 1838. Together they form the most prestigious of the society's awards. They are given for "the encouragement and promoti ...

of the Royal Geographical Society in 1876.

Forrest became involved in politics through his promotion to surveyor-general, a powerful position that entitled him to a seat on the colony's executive council. He was appointed as Western Australia's first premier in 1890, following the granting of responsible government. The gold rushes of the early 1890s saw a large increase in the colony's population and allowed for a program of public works, including the construction of Fremantle Harbour

Fremantle Harbour is Western Australia's largest and busiest general cargo port and an important historical site. The inner harbour handles a large volume of sea containers, vehicle imports and livestock exports, cruise shipping and naval vi ...

and the Goldfields Water Supply Scheme

The Goldfields Water Supply Scheme is a pipeline and dam project that delivers potable water from Mundaring Weir in Perth to communities in Western Australia's Eastern Goldfields, particularly Coolgardie and Kalgoorlie. The project was co ...

. Forrest's government also passed a number of social reforms, maintaining power through several elections in an era before formal political parties. His support for Federation

A federation (also known as a federal state) is a political entity characterized by a union of partially self-governing provinces, states, or other regions under a central federal government ( federalism). In a federation, the self-govern ...

was crucial in Western Australia's decision to join as an original member.

In 1901, Forrest was invited to join Prime Minister Edmund Barton's inaugural federal cabinet. He was a member of all but one non-Labor

Labour or labor may refer to:

* Childbirth, the delivery of a baby

* Labour (human activity), or work

** Manual labour, physical work

** Wage labour, a socioeconomic relationship between a worker and an employer

** Organized labour and the la ...

government over the following two decades, serving as Postmaster-General

A Postmaster General, in Anglosphere countries, is the chief executive officer of the postal service of that country, a ministerial office responsible for overseeing all other postmasters. The practice of having a government official responsible ...

(1901), Minister for Defence

{{unsourced, date=February 2021

A ministry of defence or defense (see spelling differences), also known as a department of defence or defense, is an often-used name for the part of a government responsible for matters of defence, found in states ...

(1901–1903), Minister for Home Affairs

An interior minister (sometimes called a minister of internal affairs or minister of home affairs) is a cabinet official position that is responsible for internal affairs, such as public security, civil registration and identification, emergenc ...

(1903–1904), and Treasurer

A treasurer is the person responsible for running the treasury of an organization. The significant core functions of a corporate treasurer include cash and liquidity management, risk management, and corporate finance.

Government

The treasury ...

(1905–1907, 1909–1910, 1913–1914, 1917–1918). He helped shape Australia's early defence and financial policies, also lobbying for the construction of the Trans-Australian Railway

The Trans-Australian Railway, opened in 1917, runs from Port Augusta in South Australia to Kalgoorlie in Western Australia, crossing the Nullarbor Plain in the process. As the only rail freight corridor between Western Australia and the east ...

, a pet project. Forrest served briefly as acting prime minister

An acting prime minister is a cabinet member (often in Westminster system countries) who is serving in the role of prime minister, whilst the individual who normally holds the position is unable to do so. The role is often performed by the deput ...

in 1907 and in 1913 was defeated for the leadership of the Liberal Party

The Liberal Party is any of many political parties around the world. The meaning of ''liberal'' varies around the world, ranging from liberal conservatism on the right to social liberalism on the left.

__TOC__ Active liberal parties

This is a li ...

by a single vote. He was nominated to the peerage in 1918 by Prime Minister Billy Hughes, but died on his way to England before the appointment could be confirmed.

Early life

Birth and family background

Forrest was born on 22 August 1847 on his father's property outside ofBunbury, Western Australia

Bunbury is a coastal city in the Australian state of Western Australia, approximately south of the state capital, Perth. It is the state's third most populous city after Perth and Mandurah, with a population of approximately 75,000.

Located a ...

. He was the fourth of ten children and third of nine sons born to Margaret (née Hill) and William Forrest. The couple's first child and only daughter, Mary, died as an infant. John's younger brothers included Alexander

Alexander is a male given name. The most prominent bearer of the name is Alexander the Great, the king of the Ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia who created one of the largest empires in ancient history.

Variants listed here are Aleksandar, Al ...

and David Forrest, who became public figures in their own right.

Forrest's parents had arrived from Scotland in December 1842, accompanying Dr John Ferguson to work as domestic servants on his farm in the newly settled district of Australind

Australind is a town in Western Australia, located 12 km north-east of Bunbury's central business district. Its local government area is the Shire of Harvey. At the 2016 census, Australind had a population of 14,539.

History

Prior to Eur ...

. Margaret was from Dundee and William from Kincardineshire

Kincardineshire, also known as the Mearns (from the Scottish Gaelic meaning "the Stewartry"), is a historic county, registration county and lieutenancy area on the coast of northeast Scotland. It is bounded by Aberdeenshire on the north and ...

; the Forrest paternal line originated from the village of Glenbervie

Glenbervie (Scottish Gaelic: ''Gleann Biorbhaidh'', Scots: ''Bervie'') is located in the north east of Scotland in the Howe o' the Mearns, one mile from the village of Drumlithie and eight miles south of Stonehaven in Aberdeenshire. The river ...

. They were released from Ferguson's service in 1846, and William took up a property at the mouth of the Preston River

The Preston River is a river in the South West region of Western Australia.

The river has a total length of and rises near Goonac siding then flows in a north-westerly direction until discharging into the Leschenault Estuary. The headwaters ...

on the eastern side of the Leschenault Estuary

Leschenault Estuary is an estuarine lagoon that lies to the north of Bunbury, Western Australia.

It had in the past met the Indian Ocean at the Leschenault Inlet, but that has been altered by harbour works for Bunbury, and the creation of The Cu ...

. He built a windmill and a small house, where John was born.

Childhood and education

A few years after Forrest's birth, the family moved down the Preston River to Picton, where William built a homestead andwatermill

A watermill or water mill is a mill that uses hydropower. It is a structure that uses a water wheel or water turbine to drive a mechanical process such as milling (grinding), rolling, or hammering. Such processes are needed in the production of ...

. The family's youngest son, Augustus, drowned in the mill race

A mill race, millrace or millrun, mill lade (Scotland) or mill leat (Southwest England) is the current of water that turns a water wheel, or the channel ( sluice) conducting water to or from a water wheel. Compared with the broad waters of a m ...

as a toddler. The mill was primarily used as a flour mill

A gristmill (also: grist mill, corn mill, flour mill, feed mill or feedmill) grinds cereal grain into flour and middlings. The term can refer to either the grinding mechanism or the building that holds it. Grist is grain that has been separated ...

, at a time when flour was a scarce commodity, but was also used as a sawmill

A sawmill (saw mill, saw-mill) or lumber mill is a facility where logs are cut into lumber. Modern sawmills use a motorized saw to cut logs lengthwise to make long pieces, and crosswise to length depending on standard or custom sizes (dimensi ...

. Its success allowed William to expand his land holdings to and gave the family a high social status in the small district around Bunbury. The property remains in the ownership of his descendants and is now heritage-listed.

Forrest and his brothers began their education at the one-room school

One-room schools, or schoolhouses, were commonplace throughout rural portions of various countries, including Prussia, Norway, Sweden, the United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, Ireland, and Spain. In most rural and s ...

in Bunbury, walking or riding in each direction. His parents prized education, and in 1860 he was sent to Perth

Perth is the capital and largest city of the Australian state of Western Australia. It is the fourth most populous city in Australia and Oceania, with a population of 2.1 million (80% of the state) living in Greater Perth in 2020. Perth i ...

to board at Bishop Hale's School, the only secondary school in the colony. He attended the school for four years, winning several prizes for arithmetic. Although three of William Forrest's sons became members of parliament, he had no involvement in public life beyond a local level and was not known to hold strong political opinions. According to John Forrest's biographer Frank Crowley, "William Forrest's greatest gift to his sons was not a precise political creed but the practical approach to life that he had acquired as a tradesman, farmer and jack-of-all-trades".

Early career

In November 1863, aged 16, Forrest took up an apprenticeship with Thomas Campbell Carey, the government surveyor at Bunbury. He had already been taught celestial navigation by his father, and under Carey learned the basic techniques of surveying, becoming proficient in traversing and the use of surveyors' tools, including Gunter's chains,prismatic compass

A prismatic compass is a navigation and surveying instrument which is extensively used to find out the bearing of the traversing and included angles between them, waypoints (an endpoint of the lcourse) and direction. Compass surveying is a type ...

es, sextants, and transit theodolites. He was also a skilled horseman and able to endure long periods in the bush without access to fresh meat and vegetables.

After two years as an apprentice to Carey, Forrest was appointed as a government surveyor on a provisional basis. He was the first person born in Western Australia to qualify as a surveyor. His term of employment began on 28 December 1865, at the age of 18, and he was assigned three assistants – a chainer, a camp-keeper, and a convict

A convict is "a person found guilty of a crime and sentenced by a court" or "a person serving a sentence in prison". Convicts are often also known as " prisoners" or "inmates" or by the slang term "con", while a common label for former conv ...

on probation. Although he was headquartered in Bunbury, Forrest spent most of his time in the field, surveying the Nelson

Nelson may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* ''Nelson'' (1918 film), a historical film directed by Maurice Elvey

* ''Nelson'' (1926 film), a historical film directed by Walter Summers

* ''Nelson'' (opera), an opera by Lennox Berkeley to a lib ...

, Sussex, and Wellington

Wellington ( mi, Te Whanganui-a-Tara or ) is the capital city of New Zealand. It is located at the south-western tip of the North Island, between Cook Strait and the Remutaka Range. Wellington is the second-largest city in New Zealand by metr ...

land districts. His position was made permanent in July 1866, and he spent most of the next two years in the Avon Valley.

Marriage

On 2 September 1876 in Perth, Forrest married Margaret Elvire Hamersley. The Hamersleys were a very wealthy family, and Forrest gained substantially in wealth and social standing from the marriage. However, to their disappointment the marriage was childless. Despite not having direct descendants his family has continued to be influential in Western Australia via his nephewMervyn Forrest

Robert Mervyn Forrest (28 April 1891 – 22 August 1975) was an Australian pastoralist and politician who served as a Liberal Party member of the Legislative Council of Western Australia from 1946 to 1952, representing North Province.

Early l ...

and Mervyn's grandson mining billionaire Andrew Forrest

John Andrew Henry Forrest (born 18 November 1961), nicknamed Twiggy, is an Australian businessman. He is best known as the former CEO (and current non-executive chairman) of Fortescue Metals Group (FMG), and has other interests in the mining i ...

.

Explorer

Between 1869 and 1874, Forrest led three expeditions into the uncharted land surrounding the colony of Western Australia. In 1869, he led a fruitless search for the explorer

Between 1869 and 1874, Forrest led three expeditions into the uncharted land surrounding the colony of Western Australia. In 1869, he led a fruitless search for the explorer Ludwig Leichhardt

Friedrich Wilhelm Ludwig Leichhardt (), known as Ludwig Leichhardt, (23 October 1813 – c. 1848) was a German explorer and naturalist, most famous for his exploration of northern and central Australia.Ken Eastwood,'Cold case: Leichhardt's dis ...

in the desert west of the site of the present town of Leonora. The following year, he surveyed Edward John Eyre

Edward John Eyre (5 August 181530 November 1901) was an English land explorer of the Australian continent, colonial administrator, and Governor of Jamaica.

Early life

Eyre was born in Whipsnade, Bedfordshire, shortly before his family moved t ...

's land route, from Perth to Adelaide

Adelaide ( ) is the capital city of South Australia, the state's largest city and the fifth-most populous city in Australia. "Adelaide" may refer to either Greater Adelaide (including the Adelaide Hills) or the Adelaide city centre. The dem ...

. In 1874, he led a party to the watershed of the Murchison River and then east through the unknown desert centre of Western Australia. Forrest published an account of his expeditions, ''Explorations in Australia'', in 1875. In 1882, he was made a Commander of the Order of St Michael and St George (CMG) by Queen Victoria

Victoria (Alexandrina Victoria; 24 May 1819 – 22 January 1901) was Queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland from 20 June 1837 until her death in 1901. Her reign of 63 years and 216 days was longer than that of any previo ...

for his services in exploring the interior.

Search for Ludwig Leichhardt

In March 1869, Forrest was asked to lead an expedition in search of Leichhardt, who had been missing since April 1848. A few years earlier, a party of Aborigines had told the explorer Charles Hunt that a group of white men had been killed by Aborigines a long time ago, and some time afterwards, anAboriginal tracker

Aboriginal trackers were enlisted by Europeans in the years following British colonisation of Australia, to assist them in exploring the Australian landscape. The excellent tracking skills of these Aboriginal Australians were advantageous to set ...

named Jemmy Mungaro had corroborated their story and claimed to have personally been to the location. Since it was thought that these stories might refer to Leichhardt's party, Forrest was asked to lead a party to the site, with Mungaro as their guide and there to search for evidence of Leichhardt's fate.

Forrest assembled a party of six, including the Aboriginal trackers Mungaro and Tommy Windich, and they left Perth on 15 April 1869. They headed in a north-easterly direction, passing through the colony's furthermost sheep station on 26 April. On 6 May, they encountered a group of Aborigines who offered to guide the party to a place where there were many skeletons of horses. Forrest's team accompanied this group in a more northerly direction, but after a week of travelling it became clear that their destination was Poison Rock, where the explorer Robert Austin was known to have left eleven of his horses for dead in 1854. They then turned once more towards the location indicated by their guide.

The team arrived in the location to be searched on 28 May. They then spent almost three weeks surveying and searching an area of about 15,000 km2 in the desert west of the site of the present-day town of Leonora. Having found no evidence of Leichhardt's fate, and Mungaro having changed his story and admitted that he had not personally visited the site, they decided to push as far eastwards as they could on their remaining supplies. The expedition reached its furthest point east on 2 July, near the present-day site of the town of Laverton. They then turned for home, returning by a more northerly route and arriving back in Perth on 6 August.

They had been absent for 113 days, and had travelled, by Forrest's reckoning, over , most of it through uncharted desert. They had found no sign of Leichhardt, and the country over which they travelled was useless for farming. However, Forrest did report that his compass had been affected by the presence of minerals in the ground, and he suggested that the government send geologists to examine the area. Ultimately, the expedition achieved very little, but it was of great personal advantage to Forrest whose reputation with his superiors and in the community at large was greatly enhanced.

Bight crossing

Later that year, Forrest was selected to lead an expedition that would survey a land route along the

Later that year, Forrest was selected to lead an expedition that would survey a land route along the Great Australian Bight

The Great Australian Bight is a large oceanic bight, or open bay, off the central and western portions of the southern coastline of mainland Australia.

Extent

Two definitions of the extent are in use – one used by the International Hydrog ...

between the colonies of South Australia and Western Australia. Eyre had achieved such a crossing 30 years earlier, but his expedition had been poorly planned and equipped, and Eyre had nearly perished from lack of water. Forrest's expedition would follow Eyre's route, but it would be thoroughly planned and properly resourced. Also, the recent discovery of safe anchorages at Israelite Bay and Eucla would permit Forrest's team to be reprovisioned along the way by a chartered schooner ''Adur''. Forrest's brief was to provide a proper survey of the route, which might be used in future to establish a telegraph link between the colonies and also to assess the suitability of the land for pasture.

Forrest's team consisted of six men his brother Alexander was second in charge, Police constable Hector Neil McLarty

Hector Neil McLarty (15 March 1851 – 24 November 1912) was a Western Australian Police officer, and customs detective. During his service as a police officer he accompanied future Premier John Forrest on two expeditions and was in charge of the o ...

, farrier

A farrier is a specialist in equine hoof care, including the trimming and balancing of horses' hooves and the placing of shoes on their hooves, if necessary. A farrier combines some blacksmith's skills (fabricating, adapting, and adj ...

William Osborn, trackers Tommy Windich and Billy Noongale (Kickett); 15 horses. The party left Perth on 30 March 1870, and arrived at Esperance on 24 April. Heavy rain fell for much of this time.

After resting and reprovisioning, the party left Esperance on 9 May and arrived at Israelite Bay nine days later. They had encountered very little feed for their horses and no permanent water, but they managed to obtain sufficient rain water from rock water-holes. After reprovisioning, the team left for Eucla on 30 May. Again, they encountered very little feed and no permanent water, and this time the water they obtained from rock water-holes was not sufficient. They were compelled to dash more than to a spot that Eyre had found water in 1841. Having secured a water source, they rested and explored the area before moving on, eventually reaching Eucla on 2 July. At Eucla, they rested and reprovisioned and explored inland, where they found good pasture land. On 14 July, the team started the final leg of their expedition through unsettled country: from Eucla to the nearest South Australian station. During the last leg, almost no water could be found, and the team were compelled to travel day and night for nearly five days. They saw their first signs of civilisation on 18 July and eventually reached Adelaide on 27 August.

A week later, they boarded ship for Western Australia, arriving in Perth on 27 September. They were honoured at two receptions: one by the Perth City Council and a citizens' banquet at the Horse and Groom Tavern. Speaking at the receptions, Forrest was modest about his own contributions, but praised the efforts of the members of the expedition and divided a government gratuity between them.

Forrest's bight crossing was one of the most organised and best managed expeditions of his time. As a result, his party successfully completed in five months a journey that had taken Eyre twelve and arrived in good health and without the loss of a single horse. From that point of view, the expedition must be considered a success.

However, the tangible results were not great. They had not travelled far from Eyre's track, and although a large area was surveyed, only one small area of land suitable for pasture was found. A second expedition by the same team returned to the area between August and November 1871 and found further good pastures, north-north-east of Esperance.

Across interior

In August 1872, Forrest was invited to lead a third expedition, from

In August 1872, Forrest was invited to lead a third expedition, from Geraldton

Geraldton ( Wajarri: ''Jambinu'', Wilunyu: ''Jambinbirri'') is a coastal city in the Mid West region of the Australian state of Western Australia, north of the state capital, Perth.

At June 2018, Geraldton had an urban population of 37,648. ...

to the source of the Murchison River and then east through the uncharted centre of Western Australia to the overland telegraph line from Darwin to Adelaide. The purpose was to discover the nature of the unknown centre of Western Australia, and to find new pastoral land.

Forrest's team again consisted of six men, including his brother Alexander and Windich. They also had 20 horses and food for eight months. The team left Geraldton on 1 April 1874, and a fortnight later, it passed through the colony's outermost station. On 3 May the team passed into unknown land. It found plenty of good pastoral land around the headwaters of the Murchison River, but by late May, it was travelling over arid land. On 2 June, while dangerously short of water, it discovered Weld Springs, "one of the best springs in the colony" according to Forrest. This later became Well 9 of the Canning Stock Route, but it proved unreliable as a water source.

At Weld Springs, the party came into conflict with a group of Martu people. In his diary, Forrest recorded that 40 to 60 men had appeared on the hill overlooking the springs, "all plumed up and armed with spears and shields". They then rushed towards the camp brandishing spears, to which Forrest and his party responded by firing their weapons. The group retreated up the hill before charging again, and more shots were fired. On the following day, Forrest found blood near the camp, speculating that two men had been shot and at least one had suffered a severe wound. Fearing another attack, Forrest and his men constructed a stone hut (or "fort") with a thatched roof, approximately high and by in area. There were no further confrontations between the groups. According to Martu oral history, the initial conflict occurred after one of the white men approached Martu singing around a fire and was threatened with a spear. The second incident occurred after the fort was built and resulted in some of their men being killed. It has been suggested that the expedition may have intruded upon a ceremonial gathering.

Beyond Weld Springs water was extremely hard to obtain, and by 4 July the team relied on occasional thunderstorms for water. By 2 August, the team was critically short of water; a number of horses had been abandoned, and Forrest's journal indicates that the team had little confidence of survival. A few days later, it was rescued by a shower of rain. On 23 August, it was again critically short of water and half of their horses were near death, when they were saved by the discovery of Elder Springs.

Then, the land became somewhat less arid, and the risk of dying from thirst started to abate. Other difficulties continued, however: the team had to abandon more of their horses, and one member of the team suffered from scurvy and could barely walk. The team finally sighted the telegraph line near Mount Alexander on 27 September and reached Peake Telegraph Station three days later. The remainder of the journey was a succession of triumphant public receptions by passing through each country town en route to Adelaide. The team reached Adelaide on 3 November 1874, more than six months after they started from Geraldton.

From an exploration point of view, Forrest's third expedition was of great importance. A large area of previously unknown land was explored, and the popular notion of an inland sea was shown to be unlikely. However, the practical results were not great. Plenty of good pastoral land was found up to the head of the Murchison, but beyond that, the land was useless for pastoral enterprise, and Forrest was convinced that it would never be settled. Forrest also made botanical collections during the expedition that were given to Ferdinand von Mueller, who, in turn, named '' Eremophila forrestii'' in his honour.

In 1875, Forrest published ''Explorations in Australia'', an account of his three expeditions. In July 1876, he was awarded the Patron's Medal

The Royal Geographical Society's Gold Medal consists of two separate awards: the Founder's Medal 1830 and the Patron's Medal 1838. Together they form the most prestigious of the society's awards. They are given for "the encouragement and promoti ...

of the Royal Geographical Society of London. He was made a CMG by Queen Victoria in 1882 for his services in exploring the interior.

Premier

He was an outstanding surveyor, and his successful expeditions had made him a popular public figure as well. Consequently, he was promoted rapidly through the ranks of the Lands and Surveys Department, and in January 1883 he succeeded

He was an outstanding surveyor, and his successful expeditions had made him a popular public figure as well. Consequently, he was promoted rapidly through the ranks of the Lands and Surveys Department, and in January 1883 he succeeded Malcolm Fraser

John Malcolm Fraser (; 21 May 1930 – 20 March 2015) was an Australian politician who served as the 22nd prime minister of Australia from 1975 to 1983, holding office as the leader of the Liberal Party of Australia.

Fraser was raised on hi ...

in the positions of surveyor-general and commissioner of crown lands. This was one of the most powerful and responsible positions in the colony, and it accorded him a seat on the colony's Executive Council. At the same time, Forrest was nominated to the colony's Legislative Council. After Britain ceded to Western Australia the right to self-rule in 1890, Forrest was elected unopposed to the seat of Bunbury in the Legislative Assembly. On 22 December 1890, Governor William Robinson appointed Forrest the first Premier of Western Australia

The premier of Western Australia is the head of government of the state of Western Australia. The role of premier at a state level is similar to the role of the prime minister of Australia at a federal level. The premier leads the executive bra ...

. In May of the following year, he was knighted KCMG KCMG may refer to

* KC Motorgroup, based in Hong Kong, China

* Knight Commander of the Order of St Michael and St George, British honour

* KCMG-LP, radio station in New Mexico, USA

* KCMG, callsign 1997-2001 of Los Angeles radio station KKLQ (FM) ...

for his services to the colony.

The Forrest Ministry

The Forrest Ministry was the first government ministry in Western Australia, after the inauguration of responsible government. It was in government from 29 December 1890 to 14 February 1901, when it was succeeded by the Throssell Ministry follow ...

immediately embarked on a programme of large-scale public works funded by loans raised in London. Public works were greatly in demand at the time, because of the British government's reluctance to approve public spending in the colony. Under the direction of the brilliant engineer C. Y. O'Connor, many thousands of miles of railway were laid, and many bridges, jetties, lighthouses and town halls were constructed. The two most ambitious projects were the Fremantle Harbour Works, one of the few public works of the 1890s which is still in use today; and the Goldfields Water Supply Scheme

The Goldfields Water Supply Scheme is a pipeline and dam project that delivers potable water from Mundaring Weir in Perth to communities in Western Australia's Eastern Goldfields, particularly Coolgardie and Kalgoorlie. The project was co ...

, one of the greatest engineering feats of its time, in which the Helena River

The Helena River is a tributary of the Swan River in Western Australia. The river rises in country east of Mount Dale and flows north-west to Mundaring Weir, where it is dammed. It then flows west until it reaches the Darling Scarp.

It passes ...

was dammed and the water piped over to Kalgoorlie. Forrest's public works programme was generally well received, although on the Eastern Goldfields where the rate of population growth and geographical expansion far outstripped the government's ability to provide works, Forrest was criticised for not doing enough. He invited further criticism in 1893 with his infamous "spoils to the victors" speech, in which he appeared to assert that members who opposed the government were putting at risk their constituents' access to their fair share of public works.

Forrest's government also implemented a number of social reforms, including measures to improve the status of women, young girls and wage-earners. However, although Forrest did not always oppose proposals for social reform, he never instigated or championed them. Critics have therefore argued that Forrest deserves little credit for the social reforms achieved under his premiership. On political reform, however, Forrest's influence was unquestionable. In 1893, Forrest guided through parliament a number of significant amendments to the

Forrest's government also implemented a number of social reforms, including measures to improve the status of women, young girls and wage-earners. However, although Forrest did not always oppose proposals for social reform, he never instigated or championed them. Critics have therefore argued that Forrest deserves little credit for the social reforms achieved under his premiership. On political reform, however, Forrest's influence was unquestionable. In 1893, Forrest guided through parliament a number of significant amendments to the Constitution of Western Australia

Western Australia (commonly abbreviated as WA) is a state of Australia occupying the western percent of the land area of Australia excluding external territories. It is bounded by the Indian Ocean to the north and west, the Southern Ocean to th ...

, including an extension of the franchise to all men regardless of property ownership. He also had a significant role in repealing section 70 of that constitution, which had provided that 1% of public revenue should be paid to a Board (not under local political control) for the welfare of Indigenous people, and was "widely hated" by the colonists.

The major political question of the time, though, was federation. Forrest was in favour of federation, and felt that it was inevitable, but he also felt that Western Australia should not join until it obtained fair terms. He was heavily involved in the framing of the Australian Constitution, representing Western Australia at a number of meetings on federation, including the National Australasian Convention of 1891, and the Australasian Federal Convention of 1897–8. There he opposed the transfer of postal and telegraphic services to the projected Commonwealth as an "absurdity", and declared only a "lunatic" would want the federal capital located in the interior of the country. He fought hard to protect the rights of the less populous states, arguing for a strong upper house organised along state lines. He also pressed for a number of concessions to Western Australia, managing to secure the phasing out of Western Australian tariffs instead of their immediate abolition, but failing to secure the construction of a trans-Australian railway.

The proposed federation was unpopular with the section of society Forrest represented. Only two of this 30 or so supporters in parliament, he said, favoured it. And 62 percent of voters in his electorate of Bunbury were to vote No when the question was put to them by referendum. But support on the goldfields was overwhelming, and by May of 1900 it was apparent his efforts could not obtain better terms. Forrest decided on a referendum, a large majority of Western Australians voted to join the federation, and in 1901 Western Australia was an "original state" of the new Commonwealth of Australia.

Federal politics

On 30 December 1900, Forrest accepted the position of

On 30 December 1900, Forrest accepted the position of Postmaster-General

A Postmaster General, in Anglosphere countries, is the chief executive officer of the postal service of that country, a ministerial office responsible for overseeing all other postmasters. The practice of having a government official responsible ...

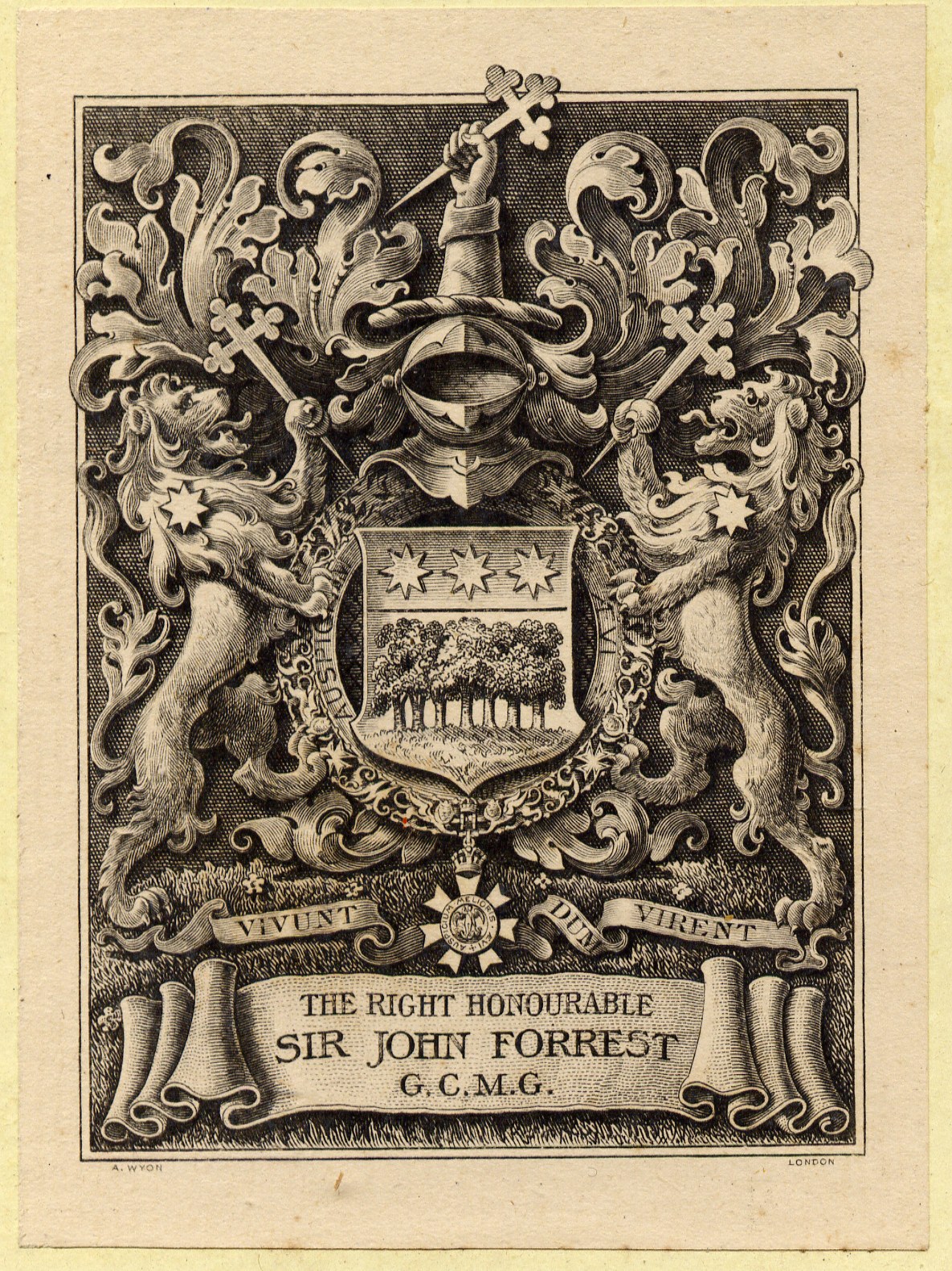

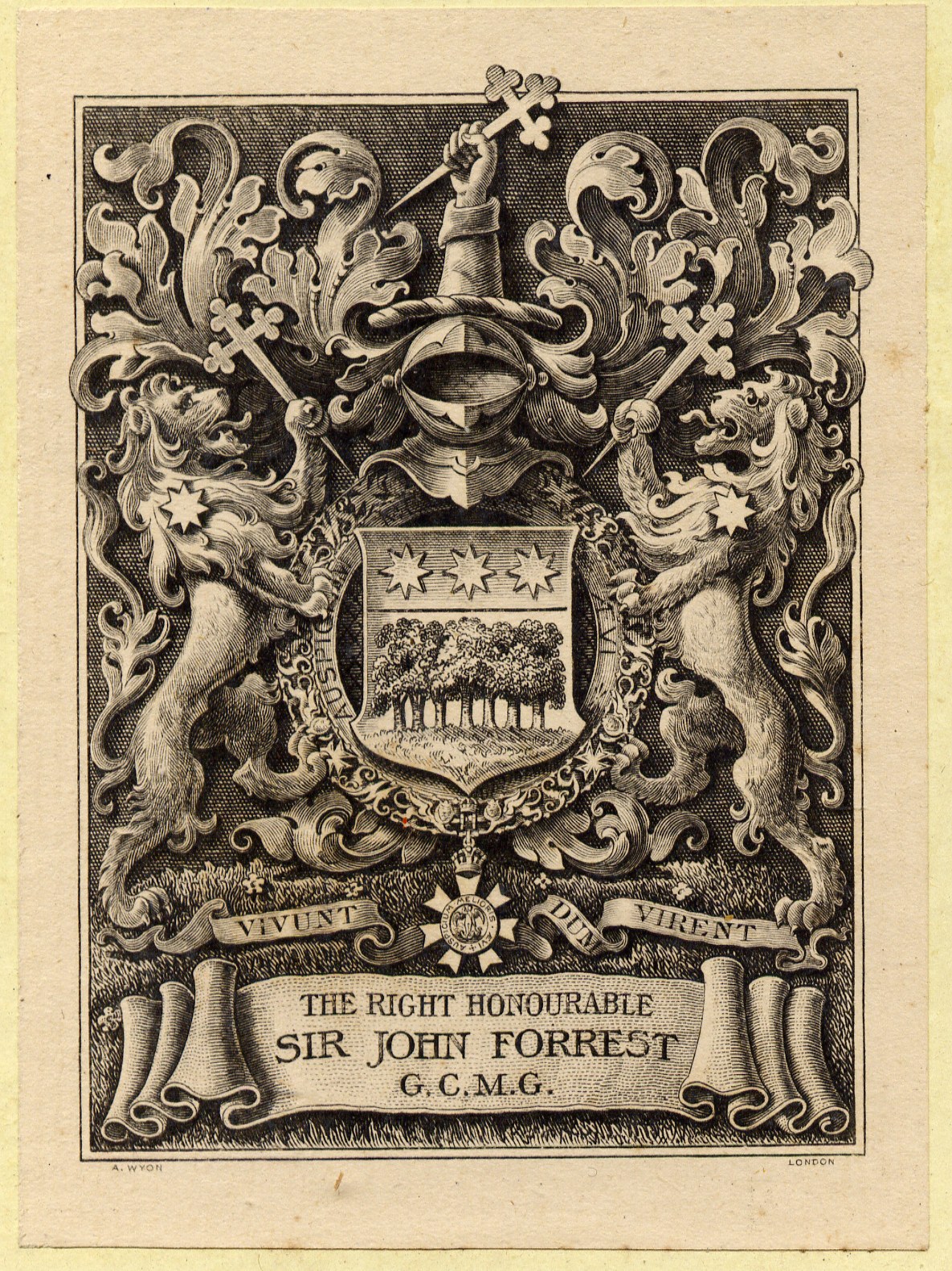

in Edmund Barton's federal caretaker government. Two days later, he received news that he had been made a GCMG

The Most Distinguished Order of Saint Michael and Saint George is a British order of chivalry founded on 28 April 1818 by George IV, Prince of Wales, while he was acting as prince regent for his father, King George III.

It is named in honour ...

"in recognition of services in connection with the Federation of Australian Colonies and the establishment of the Commonwealth of Australia". Forrest was postmaster-general for only 17 days: he resigned to take up the defence portfolio, which had been made vacant by the death of Sir James Dickson James or Jim Dickson may refer to:

Politicians

*James Dickson (Scottish politician) (c. 1715–1771), MP for Lanark Burghs 1768–1771

*James Dickson (New South Wales politician) (1813–1863), member of the New South Wales Legislative Assembly

*Ja ...

. On 13 February 1901, he resigned as premier of Western Australia and as member for Bunbury.

In the March 1901 federal election, the first one ever, Forrest was elected, unopposed, on a moderate Protectionist

Protectionism, sometimes referred to as trade protectionism, is the economic policy of restricting imports from other countries through methods such as tariffs on imported goods, import quotas, and a variety of other government regulations. ...

platform to the federal House of Representatives

House of Representatives is the name of legislative bodies in many countries and sub-national entitles. In many countries, the House of Representatives is the lower house of a bicameral legislature, with the corresponding upper house often c ...

seat of Swan. He held the defence portfolio for over two years. After a cabinet reshuffle on 7 August 1903, he became Minister for Home Affairs

An interior minister (sometimes called a minister of internal affairs or minister of home affairs) is a cabinet official position that is responsible for internal affairs, such as public security, civil registration and identification, emergenc ...

. In that portfolio, he resolutely pressed the ill-starred project to site the national capital at Dalgety, despite having previously dismissed any location within Australia's interior as lunacy.

The December 1903 federal election greatly weakened the governing party. Shortly afterwards, it was defeated and replaced by a Labour

Labour or labor may refer to:

* Childbirth, the delivery of a baby

* Labour (human activity), or work

** Manual labour, physical work

** Wage labour, a socioeconomic relationship between a worker and an employer

** Organized labour and the labour ...

government under Chris Watson. Forrest moved to the crossbenches, where he was a scathing critic of the Labour government's policies and legislation. After George Reid

Sir George Houston Reid, (25 February 1845 – 12 September 1918) was an Australian politician who led the Reid Government as the fourth Prime Minister of Australia from 1904 to 1905, having previously been Premier of New South Wales fr ...

's Free Trade Party took office in August 1904, he remained on the crossbenches but largely supported the government.

Throughout the process to select Australia's national capital site, Forrest was a firm supporter of Dalgety.

In June 1905, Alfred Deakin's Protectionist Party formed an alliance with Labour to end Reid's government. They formed a new government on 7 July, with Forrest appointed Treasurer, as fifth in seniority. After a ministerial reshuffle in October 1906, Forrest became third in cabinet precedence. He served as acting prime minister

An acting prime minister is a cabinet member (often in Westminster system countries) who is serving in the role of prime minister, whilst the individual who normally holds the position is unable to do so. The role is often performed by the deput ...

from 18 to 26 June 1907, as both Deakin and Lyne were in London attending imperial conferences.

The alliance with Labour had put Forrest in a difficult position, as he had repeatedly opposed it. Before the December 1906 federal election, he continued to attack the Labour Party despite sharing government with it and depending on its support. In the following months, Forrest was himself heavily criticised in the press for his willingness to work with the Labour Party when Cabinet was in session and for his attacks on the party during election campaigns.

He began to feel that his reputation in Western Australia and his personal standing in cabinet were being undermined. In response, he resigned as treasurer on 30 July 1907 and joined the crossbenches, where he was a mild critic of the government.

A few months later, Labour withdrew its support for Deakin's government, forcing it to resign. Labour then formed government under Andrew Fisher

Andrew Fisher (29 August 186222 October 1928) was an Australian politician who served three terms as prime minister of Australia – from 1908 to 1909, from 1910 to 1913, and from 1914 to 1915. He was the leader of the Australian Labor Party ...

. In the following months, Forrest and a number of other members worked to arrange a fusion of the Free Trade and Protectionist parties into a single party. Eventually, the Commonwealth Liberal Party

The Liberal Party was a parliamentary party in Australian federal politics between 1909 and 1917. The party was founded under Alfred Deakin's leadership as a merger of the Protectionist Party and Anti-Socialist Party, an event known as the Fus ...

was formed, with Deakin as leader. Fisher was then forced to resign, and the new Liberal Party took office on 2 June 1909, with Forrest as treasurer. Labour reclaimed office at the April 1910 federal election.

Early in 1913, Deakin resigned as Leader of the Opposition. Forrest and Joseph Cook contested the leadership, with Cook winning by a single vote. Forrest was very disappointed, especially since Deakin, whom he considered a friend, had voted against him. Five months later, in the May 1913 federal election, the Liberal Party returned to power, with Cook as Prime Minister. Forrest was appointed treasurer for the third time. However, the government's majority of just one seat in the House of Representatives, along with Labor's large majority in the Senate, made it difficult to get anything done. In June 1914, Cook asked the Governor-General for a double dissolution, and Australia was sent back to the polls. Forrest retained his seat, but the Liberal Party was soundly defeated and Forrest was again relegated to the crossbenches.

In December 1916, a split in the Labor Party over conscription left Prime Minister Billy Hughes with a minority government. Hughes and his colleagues formed the

Early in 1913, Deakin resigned as Leader of the Opposition. Forrest and Joseph Cook contested the leadership, with Cook winning by a single vote. Forrest was very disappointed, especially since Deakin, whom he considered a friend, had voted against him. Five months later, in the May 1913 federal election, the Liberal Party returned to power, with Cook as Prime Minister. Forrest was appointed treasurer for the third time. However, the government's majority of just one seat in the House of Representatives, along with Labor's large majority in the Senate, made it difficult to get anything done. In June 1914, Cook asked the Governor-General for a double dissolution, and Australia was sent back to the polls. Forrest retained his seat, but the Liberal Party was soundly defeated and Forrest was again relegated to the crossbenches.

In December 1916, a split in the Labor Party over conscription left Prime Minister Billy Hughes with a minority government. Hughes and his colleagues formed the National Labor Party

The National Labor Party was formed by Australian Prime Minister Billy Hughes in 1916, following the 1916 Labor split on the issue of World War I conscription in Australia. Hughes had taken over as leader of the Australian Labor Party and Pr ...

, and the Liberal Party joined with it in the formation of a new government. For the fourth time, Forrest was appointed treasurer. The National Labor and Liberal parties easily won a combined majority at the May 1917 election, and the two parties soon merged to form the Nationalist Party of Australia

The Nationalist Party, also known as the National Party, was an Australian political party. It was formed on 17 February 1917 from a merger between the Commonwealth Liberal Party and the National Labor Party, the latter formed by Prime Min ...

.

On 20 December, a referendum on conscription was defeated, and Hughes kept his promise to resign as prime minister if the referendum was lost. Forrest immediately declared himself a candidate for the position, but the Governor-General found that Forrest did not have the numbers and so asked Hughes to form government again. Hughes accepted, and the previous government was again sworn in.

Illness, peerage and death

Forrest had a rodent ulcer removed from his left temple in January 1915, which was initially thought to be non-malignant. Another operation followed in Perth in March 1917, but the cancer returned. He had a third operation in January 1918, after which he was hospitalised for nearly two weeks. The surgeons buried

Forrest had a rodent ulcer removed from his left temple in January 1915, which was initially thought to be non-malignant. Another operation followed in Perth in March 1917, but the cancer returned. He had a third operation in January 1918, after which he was hospitalised for nearly two weeks. The surgeons buried radium

Radium is a chemical element with the symbol Ra and atomic number 88. It is the sixth element in group 2 of the periodic table, also known as the alkaline earth metals. Pure radium is silvery-white, but it readily reacts with nitrogen (rathe ...

in the wound in that hopes that it would help prevent a recurrence. Forrest spent a month recuperating in Healesville

Healesville is a town in Victoria, Australia, 52 km north-east from Melbourne's central business district, located within the Shire of Yarra Ranges local government area. Healesville recorded a population of 7,589 in the 2021 census.

H ...

; on a visit to the Melbourne Club

The Melbourne Club is a private social club established in 1838 and located at 36 Collins Street, Melbourne.

The club is a symbol of Australia's British social heritage and was established at a gathering of 23 gentlemen on Saturday, 17 Decembe ...

during this time he was found to weigh . He resigned from the ministry on 21 March 1918, on the advice of his doctors. William Watt had been acting as treasurer in his absence and was appointed as his replacement.

On 7 February 1918, Forrest was informed by the Governor-General that he would be raised to the Peerage of the United Kingdom as a baron. The honour was granted on the advice of Hughes, who was aware that it would signal the end of Forrest's political career. It had been suggested to Hughes two years earlier by John Langdon Bonython

Sir John Langdon Bonython (;Charles Earle Funk, ''What's the Name, Please?'' (Funk & Wagnalls, 1936). 15 October 184822 October 1939) was an Australian editor, newspaper proprietor, philanthropist, journalist and politician who served a ...

. Forrest would have been the first Australian peer, and the announcement was received critically from those opposed to the granting of hereditary honours, including many of Hughes' former ALP colleagues. However, Forrest's peerage was never formalised, as no letters patent were issued before his death. His barony is not listed in ''The Complete Peerage

''The Complete Peerage'' (full title: ''The Complete Peerage of England, Scotland, Ireland, Great Britain, and the United Kingdom Extant, Extinct, or Dormant''; first edition by George Edward Cokayne, Clarenceux King of Arms; 2nd edition rev ...

''.

Faced with declining health, Forrest decided to travel to London to seek assistance from specialists in London, accompanied by his wife and a nurse. Before he left he revised his will and made arrangements for his burial. He also hoped to take his seat in the House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by appointment, heredity or official function. Like the House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminste ...

if his health permitted. Forrest left Albany aboard the troopship ''Marathon'' on 30 July 1918. He spent two nights in a private hospital when the ship stopped in Durban

Durban ( ) ( zu, eThekwini, from meaning 'the port' also called zu, eZibubulungwini for the mountain range that terminates in the area), nicknamed ''Durbs'',Ishani ChettyCity nicknames in SA and across the worldArticle on ''news24.com'' from ...

, South Africa, but returned to the ship and celebrated his 71st birthday on 22 August "in considerable pain". He died at sea on 2 September 1918, three hours away from Freetown

Freetown is the capital and largest city of Sierra Leone. It is a major port city on the Atlantic Ocean and is located in the Western Area of the country. Freetown is Sierra Leone's major urban, economic, financial, cultural, educational and po ...

, Sierra Leone

Sierra Leone,)]. officially the Republic of Sierra Leone, is a country on the southwest coast of West Africa. It is bordered by Liberia to the southeast and Guinea surrounds the northern half of the nation. Covering a total area of , Sierr ...

.

Forrest was initially interred at the military cemetery in Freetown. His body was brought back to Western Australia and buried at Karrakatta Cemetery

Karrakatta Cemetery is a metropolitan cemetery in the suburb of Karrakatta in Perth, Western Australia. Karrakatta Cemetery first opened for burials in 1899, the first being that of wheelwright Robert Creighton. Managed by the Metropolitan Ce ...

on 7 May 1919. His death occasioned the 1918 Swan by-election

The 1918 Swan by-election was a by-election for the Division of Swan in the Australian House of Representatives, following the death of the sitting member Sir John Forrest. Held on 26 October 1918, the by-election led to the election of the younge ...

, which saw the 22-year-old ALP candidate Edwin Corboy

Edwin Wilkie "Ted" Corboy (24 August 1896 – 6 August 1950) was an Australian politician. From 1918 to 2010, he held the record as the youngest ever Australian Member of Parliament#Australia, Member of Parliament.

Early life

Born in Victoria, ...

become Australia's youngest member of parliament, a record not broken until 2010.

Character

He was a tall, heavily built man; in his later years, he tended towards stoutness, and he had a mass of about when he died. He was fond of pomp and ceremony and insisted on being treated with respect at all times. Highly sensitive to criticism, he hated having his authority challenged and tended to browbeat his political opponents. He had very little sense of humour and was greatly offended when a journalist playfully referred to him as the "Commissioner for Crown Sands".

His upbringing and education were said by his biographer, F. K. Crowley, to have compounded in him "social snobbery, laissez-faire capitalism, sentimental royalism, patriotic Anglicanism, benevolent imperialism and racial superiority." He was, however, a very popular figure who treated everyone he met with politeness and dignity. He was renowned for his memory for names and faces and for his prolific letter-writing.

However, as reported in ''

He was a tall, heavily built man; in his later years, he tended towards stoutness, and he had a mass of about when he died. He was fond of pomp and ceremony and insisted on being treated with respect at all times. Highly sensitive to criticism, he hated having his authority challenged and tended to browbeat his political opponents. He had very little sense of humour and was greatly offended when a journalist playfully referred to him as the "Commissioner for Crown Sands".

His upbringing and education were said by his biographer, F. K. Crowley, to have compounded in him "social snobbery, laissez-faire capitalism, sentimental royalism, patriotic Anglicanism, benevolent imperialism and racial superiority." He was, however, a very popular figure who treated everyone he met with politeness and dignity. He was renowned for his memory for names and faces and for his prolific letter-writing.

However, as reported in ''The Ballarat Star

''The Ballarat Star'' was a newspaper in Ballarat, Victoria, Australia, first published on 22 September 1855. Its publication ended on 13 September 1924 when it was merged with its competitor, the ''Ballarat Courier''.''Ballarat Star'' Newspap ...

'' on 12 July 1907, Forrest defended the use of neckchains to restrain enslaved indigenous captives, saying "Chaining aborigines by the neck is the only effective way of preventing their escape."

Racial views

Forrest took apaternalistic

Paternalism is action that limits a person's or group's liberty or autonomy and is intended to promote their own good. Paternalism can also imply that the behavior is against or regardless of the will of a person, or also that the behavior expres ...

and patronising attitude toward Indigenous Australians

Indigenous Australians or Australian First Nations are people with familial heritage from, and membership in, the ethnic groups that lived in Australia before British colonisation. They consist of two distinct groups: the Aboriginal peoples ...

. He supported assimilation policies and his views were considered liberal by contemporary Western Australian standards. In 1883, in one of his first speeches to parliament, he referred to Aboriginal people being "hunted like dogs" and said they were owed "something more than repression". In the same speech he stated that they should not be punished too severely as they were "to a great extent like children". He further described Aboriginal people in an 1892 address to the National History Society as "in the same category as Marsupialia

Marsupials are any members of the mammalian infraclass Marsupialia. All extant marsupials are endemic to Australasia, Wallacea and the Americas. A distinctive characteristic common to most of these species is that the young are carried in a po ...

in having a very low degree of intelligence", but was impressed with their complex traditions and hoped they would be recorded before the race "died out". In 1890, he submitted an anthropological paper on marriage in north-west Australia to the Australasian Association for the Advancement of Science

The Australian and New Zealand Association for the Advancement of Science (ANZAAS) is an organisation that was founded in 1888 as the Australasian Association for the Advancement of Science to promote science.

It was modelled on the British As ...

, along with "a brief appeal to preserve the Aboriginal race and its culture from extinction".

A study by Elizabeth Goddard and Tom Stannage

Charles Thomas Stannage, AM (14 March 19444 October 2012) was a prominent Western Australian historian, academic, and Australian rules football player. He edited the major work ''A New History of Western Australia'', which was published in 198 ...

of Forrest's public statements on Aboriginal people concluded that he was "locked into and promoted an ideology of development which had racism at its heart". In 1886, as surveyor-general, he introduced the '' Aborigines Protection Act 1886'' into the Legislative Council, which provided for an Aborigines Protection Board. He was appointed to the board in 1890, by which time it had been given a fixed percentage of the colony's annual revenue in the newly granted constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When these princ ...

. Forrest was strongly opposed to the financial provisions and after becoming premier sought to amend the constitution to remove them. He spent several years lobbying the British government for approval, which was eventually granted in 1897 and saw Aboriginal affairs return to the control of the colonial government. According to Martyn Webb

Martyn Jack Webb (29 September 1925 – 19 January 2016) was a professor of geography and writer on issues of governance.

An Oxford graduate, he was foundation Professor of Geography at the University of Western Australia. Robson ALecture theatr ...

, he was capable of compassion towards Aboriginal people, but "it would be wrong to imagine that Forrest was some sort of unrequited idealist as far as Aborigines were concerned" and "his views about Aboriginal people as a whole were not entirely different from those of his time".

As premier, Forrest faced pressure from pastoralists in the north-west – including family members and parliamentary colleagues – to intervene on their behalf in frontier conflicts, simultaneously facing pressure to intervene in cases of cruelty and mistreatment toward Aboriginal people. In 1893, on the topic of massacres

A massacre is the killing of a large number of people or animals, especially those who are not involved in any fighting or have no way of defending themselves. A massacre is generally considered to be morally unacceptable, especially when per ...

, he stated that "I must not, in the position I am in, do anything or sanction anything that will lead to the impression that an indiscriminate slaughter of blackfellows will be tolerated or allowed by the government of the colony". In 1889 he had persuaded the Executive Council to commute a death sentence imposed on an Aboriginal man in Roebourne, who had been convicted of murder for a killing under customary law. Forrest's government nevertheless introduced harsher penalties for Aboriginal people caught stealing or killing livestock, including flogging and imprisonment. It also continued the use of Rottnest Island

Rottnest Island ( nys, Wadjemup), often colloquially referred to as "Rotto", is a island off the coast of Western Australia, located west of Fremantle. A sandy, low-lying island formed on a base of aeolianite limestone, Rottnest is an A-class ...

as a prison for Aboriginal offenders, despite his earlier criticism of the practice of taking them away from their home country. In 1905 he defended the use of neck chains for Aboriginal prisoners, stating that were necessary to prevent escape.

Legacy

Forrest's legacy can be found in the Western Australian landscape, with many places named by or after him:

* the small settlement of Forrest on the

Forrest's legacy can be found in the Western Australian landscape, with many places named by or after him:

* the small settlement of Forrest on the Trans-Australian Railway

The Trans-Australian Railway, opened in 1917, runs from Port Augusta in South Australia to Kalgoorlie in Western Australia, crossing the Nullarbor Plain in the process. As the only rail freight corridor between Western Australia and the east ...

;

* Glen Forrest;

* Forrestdale;

* John Forrest National Park

John Forrest National Park is a national park in the Darling Scarp, east of Perth, Western Australia. Proclaimed as a national park in November 1900, it was the first national park in Western Australia and the second in Australia after Royal Nat ...

;

* Forrest River

The Forrest River is a river in the Kimberley region of Western Australia.

The river rises just east of Pseudomys Hill in the Drysdale River National Park and flows in an easterly direction until discharging into the western arm of the Cambri ...

;

* Forrest Chase

Forrest Chase is a major shopping centre in Perth, Western Australia located in Forrest Place.

A Myer store serves as its main anchor and largest tenant. The centre also contains a Woolworths supermarket and other shops. The western portion of ...

;

* Forrestfield and

* John Forrest Secondary College in Morley Morley may refer to:

Places England

* Morley, Norfolk, a civil parish

* Morley, Derbyshire, a civil parish

* Morley, Cheshire, a village

* Morley, County Durham, a village

* Morley, West Yorkshire, a suburban town of Leeds and civil parish

* M ...

.

In addition, the electoral Division of Forrest was created in 1922; the suburb of Forrest, Australian Capital Territory

Forrest (postcode: 2603) is a suburb of Canberra, Australian Capital Territory, Australia. Forrest is named after Sir John Forrest, an explorer, legislator, federalist, Premier of Western Australia, and one of the fathers of the Australian Const ...

is named after Forrest, as one of the many suburbs of Canberra named after Australia's first federal politicians.

The Forrest Highway

Forrest Highway is a highway in Western Australia's Peel and South West regions, extending Perth's Kwinana Freeway from east of Mandurah down to Bunbury. Old Coast Road was the original Mandurah–Bunbury route, dating back to the 1840s. ...

, opened in September 2009, was named after him. The Eyre Highway

Eyre Highway is a highway linking Western Australia and South Australia via the Nullarbor Plain. Signed as National Highways 1 and A1, it forms part of Highway 1 and the Australian National Highway network linking Perth and Adelaide. It ...

was first known as the Forrest Highway, when it was first established as an unsealed road in 1942.

He is one of many railroad builders featured as a possible computer-controlled competitor in the simulation game Railroad Tycoon 3

''Railroad Tycoon 3'' is a video game, part of the '' Railroad Tycoon'' series, that was released in 2003.

Gameplay

With nearly 60 locomotives in the game (nearly 70 in the Coast to Coast expansion), the game has the most locomotives of the Rail ...

.

On 28 November 1949, the Australian post office issued a commemorative stamp that featured Forrest.

The Lord Forrest Hotelhttp://www.lordforresthotel.com.au opened in Bunbury in 1986 even though he was never correctly known by that name. It is still running today and proudly displays his pictures on the walls. It is the largest hotel in Bunbury.

References

Further reading

* * * * * * * *External links

* *Forrest, John (Sir) (1847–1918)

National Library of Australia, ''Trove, People and Organisation'' record for John Forrest * {{DEFAULTSORT:Forrest, John 1847 births 1918 deaths Australian explorers Burials at Karrakatta Cemetery Deaths from cancer Colonial Secretaries of Western Australia Commonwealth Liberal Party politicians Explorers of Western Australia People educated at Hale School Australian Knights Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George Australian politicians awarded knighthoods Members of the Australian House of Representatives for Swan Members of the Australian House of Representatives Members of the Cabinet of Australia Australian members of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom Members of the Western Australian Legislative Assembly Members of the Western Australian Legislative Council People from Bunbury, Western Australia Premiers of Western Australia Protectionist Party members of the Parliament of Australia Surveyors General of Western Australia Treasurers of Australia Australian federationists People who died at sea Treasurers of Western Australia Independent members of the Parliament of Australia Commonwealth Liberal Party members of the Parliament of Australia Nationalist Party of Australia members of the Parliament of Australia Defence ministers of Australia Goldfields Water Supply Scheme 20th-century Australian politicians